10.HILMA AF KLINT

Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future

When Hilma af Klint began creating radically abstract paintings in 1906, they were like little that had been seen before: bold, colorful, and untethered from any recognizable references to the physical world. It was years before Vasily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich, Piet Mondrian, and others would take similar strides to rid their own artwork of representational content. Yet while many of her better-known contemporaries published manifestos and exhibited widely, af Klint kept her groundbreaking paintings largely private. She rarely exhibited them and, convinced the world was not yet ready to understand her work, stipulated that it not be shown for twenty years following her death. Ultimately, her work was all but unseen until 1986, and only over the subsequent three decades have her paintings and works on paper begun to receive serious attention.

HILMA AF KLINT AND HER CONTEMPORARIES

Hilma af Klint (1862-1944) made her international debut with the exhibition The Spiritual in Art – Abstract Paintings 1890 – 1985, held at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art during the winter of 1986. This travelling exhibition continued to Chicago and to Haag in the Netherlands, and marked the beginning of Hilma af Klint’s international recognition. The works of Hilma af Klint have since been displayed in many exhibitions in the Nordic countries, in Europe and in the Unites States. In 2013, the Museum of Modern Art in Stockholm held the as of yet largest retrospective exhibition of the artist, featuring a collection of approximately 230 paintings. After Stockholm, the exhibition continued as a travelling exhibition throughout Europe, and was seen by more than a million visitors in total. It made a significant impact, not the least through the multidisciplinary research it initiated.

Hilma af Klint belonged to one of the first generations of women to receive a higher education at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts (Kungl. Konstakademien) in Stockholm. She was accepted into the Royal Academy of Fine Arts at the age of twenty. During the years 1882-1887 she studied there, she was mainly drawing, and portrait- and landscape painting. Hilma af Klint graduated with honors, and was awarded a scholarship in the form of a studio in the so called “Atelier Building” (Ateljébyggnaden), owned by The Academy of Fine Arts, in the crossing between Hamngatan and Kungsträdgården in central Stockholm. This was the main cultural hub in the Swedish capital at that time. The same building also held Blanchs Café and Blanchs Art Gallery, where the conflict stood between the conventional art view of the Academy of Fine Arts, and the opposition movement of the Art Society (Konstnärsförbundet), inspired by the French En Plein Air painters.

Hilma af Klint worked in this studio until 1908, when she had to move in order to take care of her blind mother. She would dutifully restrain her freedom and independence during several years in order to assist her sick mother. In her youth, Hilma af Klint is said to have had an amorous affair with a certain Dr Helleday, but as this didn’t result in anything, she decided to remain unmarried all her life. In 1917 Hilma af Klint inaugurated her new studio at Munsö, close to Adelsö, an island in the lake Mälaren not far from Stockholm, where the family had a mansion. After her mother had passed away in 1920, she moved to Helsingborg in the South of Sweden. From 1935 she lived in Lund. Nine years later, when she was more than 80 years old, Hilma af Klint moved back up to Stockholm, where she stayed in the house of her cousin, Hedvig af Klint in Ösby, Djursholm.

Hilma af Klint died in the autumn of 1944, at nearly 82 years old, following a traffic accident.

Like many of her contemporaries at the turn of last century, Hilma af Klint was in search of spiritual insight. As a teenager she participated in spiritistic séances, but gave them up due to their lack of seriousness. In her thirties, Hilma af Klint was a member of the Edelweiss Society for a short while. The Rosicrucian Order also constituted a major source of inspiration for her. Above all, Hilma af Klint was heavily involved in the Theosophical Society, of which she was member from the very start in Sweden in 1889. In her sixties, she also became interested in anthroposophy.

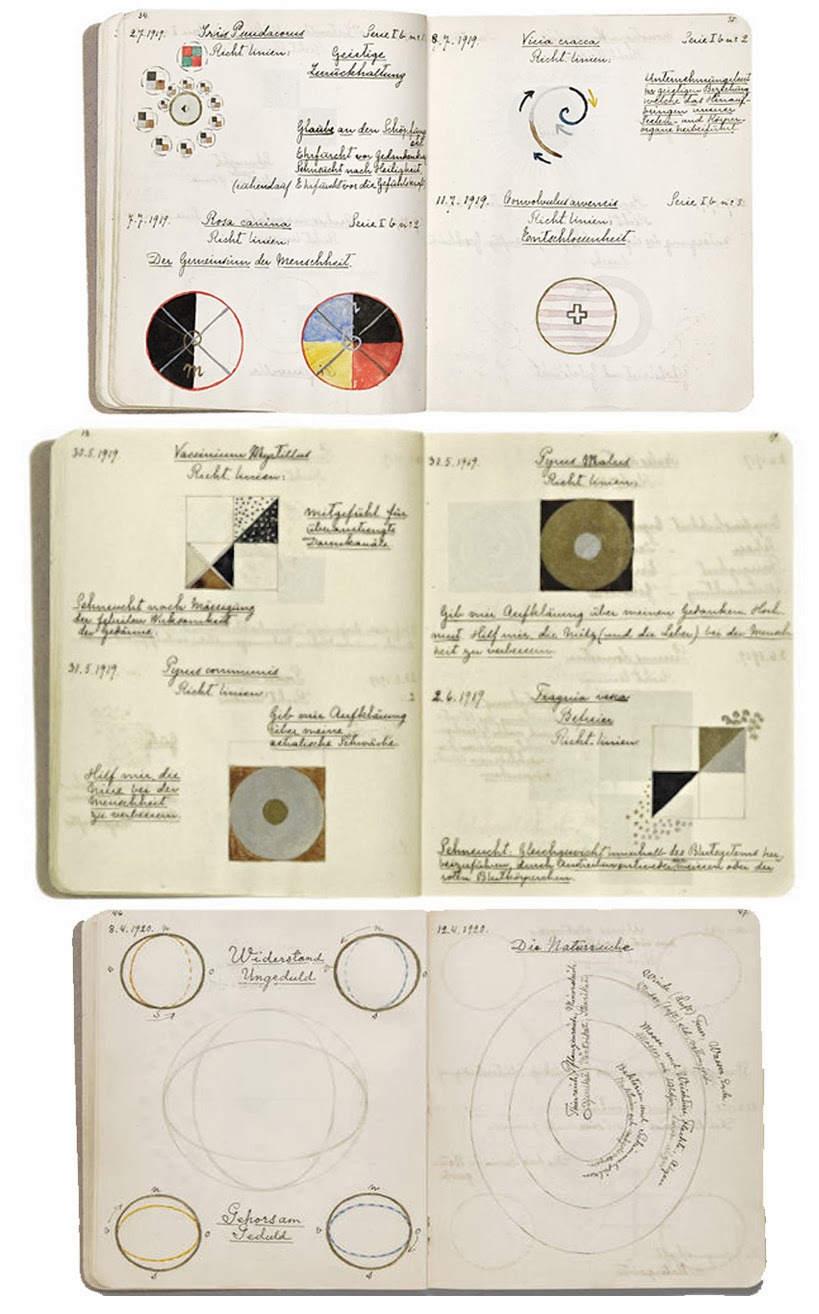

In 1896 Hilma af Klint and four other like-minded female artists left the Edelweiss Society and founded the “Friday Group”, also called “The Five”. They met every Friday for spiritual meetings, which started with prayers, studies of the New Testament and meditation, followed by spiritual séances. The medium exercised automatic writings and mediumistic drawings. They progressively made contact with spiritual beings, whom they called “The High Ones” (De Höga). In 1896, the five women started taking meticulous notes of the mediumistic messages that the spirits conveyed to them. With time, Hilma af Klint felt herself selected for the more important messages. After ten years of esoteric training within the frame of “The Five”, and at the age of 43, Hilma af Klint accepted to carry out a major assignment, the “Paintings for the Temple”. This commission, in which she would be engaged between 1906 and 1915, would change the course of her life.

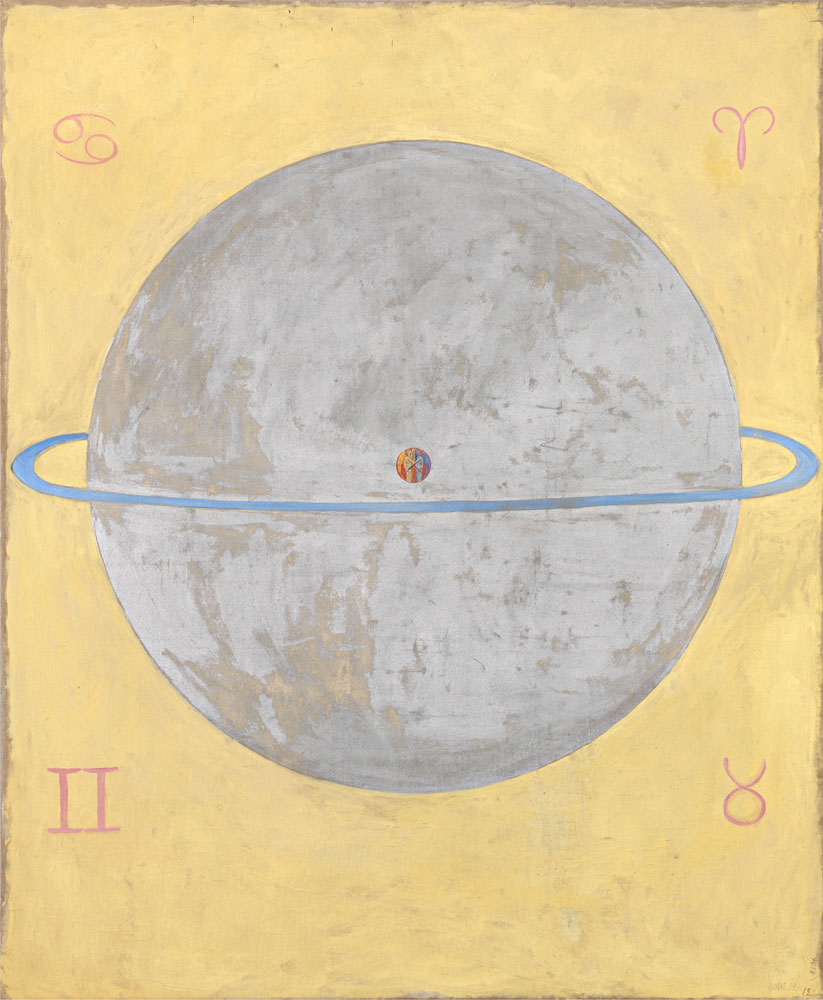

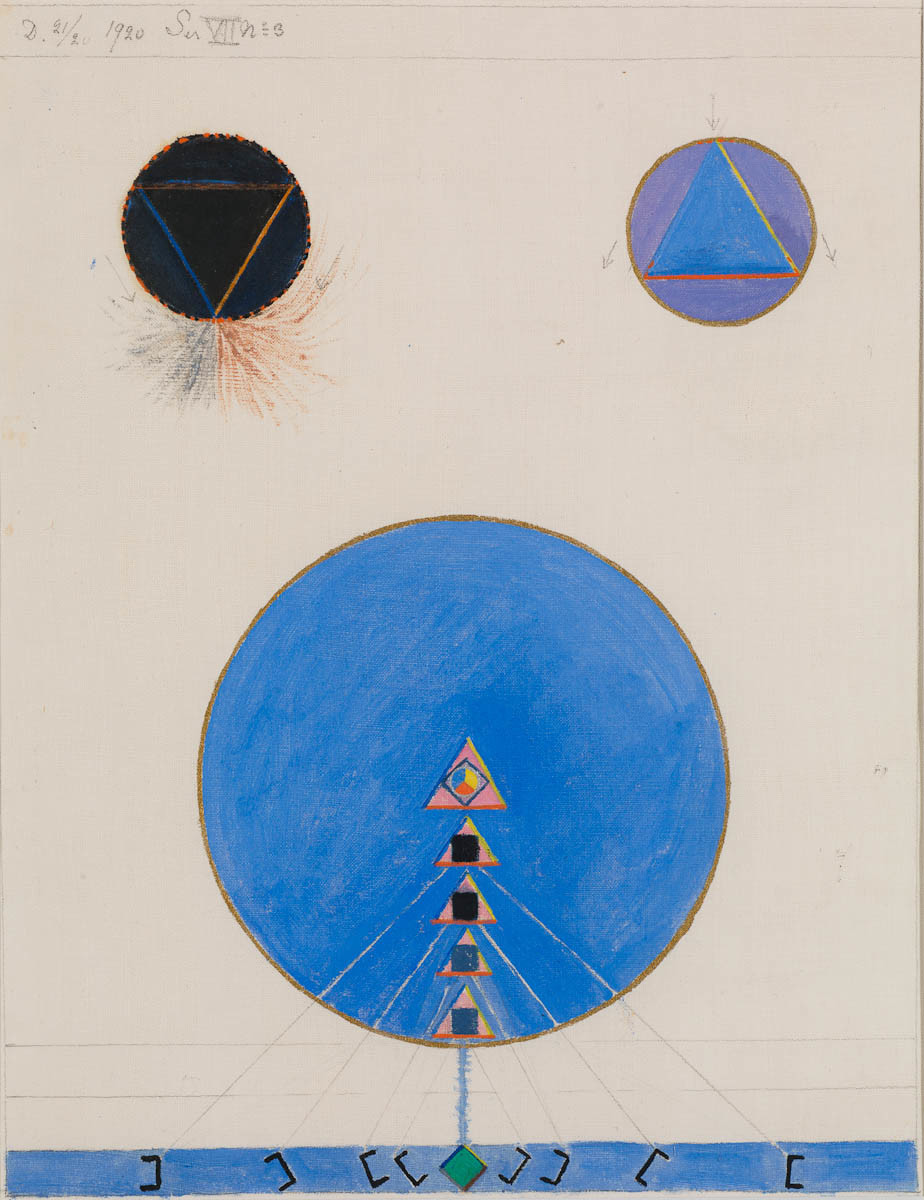

The collection “Paintings for the Temple” encompasses 193 paintings, subdivided into several series and sub-groups. It is one of the very first pieces of abstract art in the Western world, as it predates with several years the first non-figurative compositions of her contemporaries in Europe.

Hilma af Klint shared an interest in the spiritual with the other contemporary pioneers in abstract art: Wassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich, Piet Mondrian, and František Kupka among others. They all wished to surpass the restrictions of the physical world. Not surprisingly, many were drawn to Theosophy, as its ideas proposed an attractive alternative to the very static principles of the academic art. The abstract, non-figurative art opened up a radically new means of expression. Rather than depicting a mere visual impression, they aimed at finding a new path, reaching for a spiritual reality. Each one of them found his, or her, own personal way into abstract painting.

There is no evidence that Hilma af Klint was involved in the abstract movement of her male contemporary colleagues, nor that she participated in the development of early Modernism in Central and Western Europe. Nevertheless, she invented a similar, non-representational aesthetics. The contact with spiritual guides, who both inspired her and communicated with her, were for Hilma af Klint as real as the impressions given by the five physical senses. By visualizing inner processes and experiences, and by describing these as concretely and precisely as possible, she proceeded to develop a very personal expression.

Hilma af Klint was convinced that reality is not confined to the mere physical world; she was convinced that in parallel with the material world lies an inner one, and that the contents of the inner dimensions are exactly as true and real as are those of the outer one. In order to convey this message, Hilma af Klint made use of symbols, letters and words. By means of employing dualistic symbols, Hilma af Klint expressed that “Everything is Unity”.

The ambition of Hilma af Klint was to develop an artistic relation to her esoteric material, by means of an inner, spiritual maturity, and to express this in her paintings. Hilma af Klint was balancing on the edge, having to regulate inner impulses and at the same expressing them in her artistic work. Her professional ability, developed during her studies, and after working more than 20 years as an established conventional painter, was a requirement for her to succeed. She had at hand the tools necessary for concretizing her ambition.

Hilma af Klint understood the uniqueness of her works. Working intensively with herself, and with her personal development, she wanted to understand the process in which she was taking part.

This aspect became the main quest all through her life: “What is the message that the paintings convey?”. She would actively seek the answer through philosophical studies, by taking part in various religious movements and by researching in their respective archives – all in vain.

Hilma af Klint had a vision that her work would contribute to influence not only the consciousness of people in general, but in its extension also society itself. However, she was convinced that her contemporaries were not ready to perceive them. She had received strict orders from the “High Ones”, her spiritual leaders, not to show the paintings to anyone. Not even Rudolf Steiner could interpret Hilma af Klint’s paintings. At their first meeting in 1908, Rudolf Steiner consequently advised her to wait fifty years before exhibiting them. This is one of the reasons why Hilma af Klint never aimed at exhibiting her esoteric and abstract works during her lifetime. The works of art belonged to the future and would only then be understood by the public.

When Hilma af Klint passed away in the autumn of 1944, she left behind around 1300 non-figurative paintings that had never been shown to outsiders, and more than 125 notebooks and sketchbooks. In her will, Hilma af Klint specified that her life’s work should be kept secret for at least 20 years after her death. Her last wish was also that the collection should never be split up.

The collection of abstract paintings and notebooks of Hilma af Klint is today owned and managed by the Hilma af Klint Foundation in Stockholm, Sweden.

Hilma af Klint painted for the future. That future is now…

Georgiana Houghton, Hilma af Klint, and Emma Kunz explored invisible forces and the transcendental; the works presented in this exhibition are the result of spiritual experiences and communication with a higher realm. The three artists understood themselves as mediums, as recipients of messages which perhaps only they could hear and which they captured in the form of works of art. With this form of mediumistic artistic creation, the artist subject relinquishes his or her ego, hands it over, as it were, at the studio door, and acts as a mediator between a hidden and the visible world.

As “world receivers,” these artists were able to attribute the creation of their pictures to an external source. This gave them the freedom to overcome social, cultural, and aesthetic boundaries in their works, as well as the energy necessary to actually do so. This is accompanied by a delimitation of the concept of the work of art, which continues with the filmmakers: Harry Smith described his films as abstract scores, to which jazz musicians could improvise live; James Whitney understood his films as tools for meditation that could provide insight into cosmic principles; and the technical equipment developed by John Whitney is closely linked to the advent of modern computer technology.

read more: